In 2011, corruption in Egypt’s bread supply contributed to the historic ouster of President Hosni Mubarak. Yet, with limited reforms enacted since this transition, pervasive corruption in Egypt’s wheat market continues to create instability for the fragile new democracy.

View of Cairo from the center of the City.

People line up to buy bread from a bakery in downtown Cairo.

A worker in a bakery of Boulaq Abu al Ela area.

A worker in a Boulaq Abu al Ela area bakery takes a break.

Bread dough in a Boulaq Abu al Ela bakery.

A baker shakes flour from his hands

Inside a Khan el Khalili bakery in the Old Cairo.

A baker removes fresh bread from the oven in the Boulaq Abu al Ela bakery.

The manager (center) of a Boulaq Abu al Ela bakery

Fresh bread ready to sell at the Boulaq Abu al Ela bakery

Bread loaves ready to be delivered are put on the floor in a Khan el Khalili bakery

"A baker in a Boulaq Abu al Ela bakery

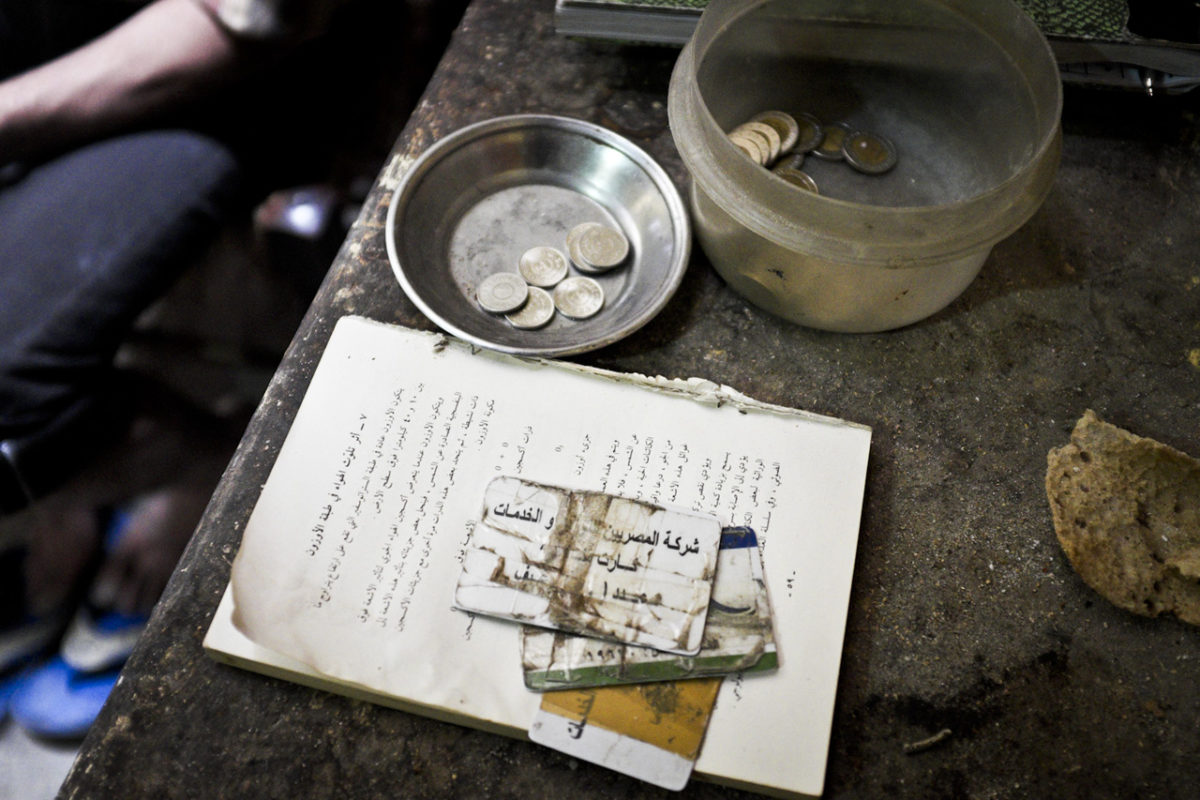

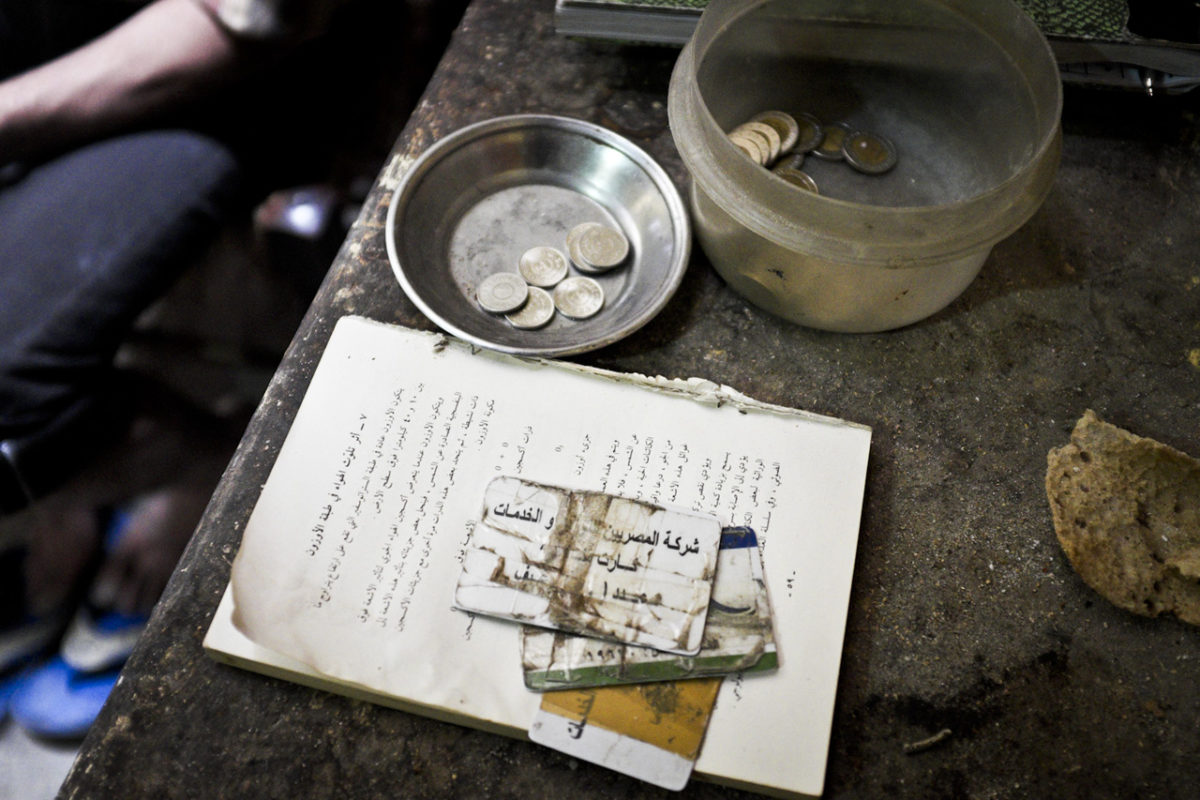

Money to buy bread at a bakery in Khan el Khalili

Bread selling kiosk in the Boulaq Abu al Ela area in the center of Cairo.

Bread selling kiosk in the Boulaq Abu al Ela area in the center of Cairo.

"Street food made of "foul" (beans)

Loaves of bread in front of a street vendor in downtown Cairo.

CAIRO—Once a bustling commercial nexus, the historic Cairene neighborhood of Imbaba now languishes in the unfulfilled promises of both dictatorship and revolution. Cast literally in the shadow of Egypt’s illustrious pyramids, the working class neighborhood has long been a hotbed of resistance and Islamist community organizing. Egypt’s political institutions have undergone radical changes in recent years; yet, for the people of Imbaba, one fundamental demand remains the same: they need bread.

“We were a part [of the 2011 ouster of Mubarak], but many from Imbaba were martyrs even before the Revolution,” explained Haditha, a mother-of-three, alluding to anti-Mubarak agitation that began in the neighborhood in the mid-1990s due to bread shortages.

“We live modest lives here, so bread has always been the most important … ‘Freedom,’ ‘dignity,’ but most importantly, ‘bread,’” she said in reference to the three demands of the 2011 protests.

In Egypt, the thin, grainy, saucer-like government-subsidized bread has played a central role in the social and political life of modern-day Egypt. Beginning in the 1950s and 60s under the socialist policies of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, food subsidies — centered around the peasants’ right to bread — became a chief pillar of Egypt’s transition from colonialism to independence. In this era, the government built infrastructure for the production and processing of wheat as well as a vast network of neighborhood distribution centers. A combination of foreign aid and local revenues buoyed the new, massive, nation-wide public assistance program

“Egypt’s economic strategy at the time was one of import substitution — a policy in which the government creates tariffs and other protective economic policies in order to support the development of local industry,” explained Dr. Ashraf el-Sherif of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “In the case of wheat, however, Egypt was nearly, but not quite, self-sufficient and subsequently agreed to limited trade with the United States to support its subsidy program.”

Since this period, however, Egypt’s population has soared to more than 80 million people, with an additional 1.5 million added per year due to the country’s high birthrates. That population swell, coupled with the country’s historic institutional promise of bread, has led Egypt to be the world’s largest importer of wheat.

For many, the bread subsidy is fundamental to daily life. Nearly 20 percent of Egypt’s population lives with less than a dollar per day, relying on bread for about one-third of their daily caloric intake and nearly half of their total daily protein consumption. When wheat supplies run short, social upheaval is virtually inevitable in neighborhoods like Imbaba.

“It becomes the people’s only option for survival,” explained Haditha, referring to the 2008 bread shortages that left at least 11 Egyptians dead from fights, accidents, exhaustion or heart attack in bread lines.

Politicians have been keenly aware of the political implications of subsidy reforms since as early as 1977, when an attempt to eliminate the subsidy resulted in the famous “bread riots”that left more than 80 people dead and required army intervention.

Egyptian officials had long hoped that the bloated market share of Egypt’s demand would create a competitive bidding process among the world’s wheat suppliers, relying upon the invisible hand of the market to drive down the price.

Yet, Egypt’s relatively weak economy combined with intense domestic pressure for a steady supply, have made self-sufficiency impossible.

As a result, Egypt spends over $3 billion per year on its subsidized wheat program, a harrowing portion of its domestic budget, with the majority of that supply coming from more expensive foreign sources, like the United States and Russia. According to a government spokesperson, an estimated 7 million Egyptian poundsworth of the subsidies are lost in corruption annually.

In early 2013, a comprehensive journalistic investigation, conducted by investigative reporters of Cairo’s Belail Media Company, sought to produce an independent exploration of Egypt’s domestic bread supply. The investigation included interviews with the government and with workers at every point in the supply chain.

The documentary encouraged a national conversation about many issues surrounding the nation’s bread supply, most significantly the potential for self-sufficiency in domestic wheat production for at least the subsidized demand. According to the International Grains Council, Egypt has the potential to produce 9.4 million tons of wheat annually — more than half of Egypt’s national demand in terms of consumption and more than the total domestic subsidy program.

In other words, Egypt’s domestic wheat production — from the fields to the mills to the bakeries — has the potential to fulfill the supply needed to satisfy the domestic demand for subsidized bread.

By curbing domestic corruption and other failures in the production and supply-chain, Egypt’s domestic wheat production alone could eliminate the costs associated with the government’s dependence on more expensive foreign wheat. Aside from fuel, wheat currently represents the largest single subsidy expenditure in the Egyptian budget annually and comprises the bulk of the $4.6bn that Egypt spends annually on food imports.

For Haditha, corruption is an endemic part of the bread subsidy. For six years, she claimed that she and her family paid an additional fee to the local bakery, which refused to sell the subsidized bread without it. She recalled how a local resident used his mobile phone to film the baker bribing a government official — only to be chased down and then arrested on false charges by police.

“Even if we switch bakeries, we would find the same games,” Haditha sighed, motioning toward the breadlines that extended down the street.

View of Cairo from the center of the City.

People line up to buy bread from a bakery in downtown Cairo.

A worker in a bakery of Boulaq Abu al Ela area.

A worker in a Boulaq Abu al Ela area bakery takes a break.

Bread dough in a Boulaq Abu al Ela bakery.

A baker shakes flour from his hands

Inside a Khan el Khalili bakery in the Old Cairo.

A baker removes fresh bread from the oven in the Boulaq Abu al Ela bakery.

The manager (center) of a Boulaq Abu al Ela bakery

Fresh bread ready to sell at the Boulaq Abu al Ela bakery

Bread loaves ready to be delivered are put on the floor in a Khan el Khalili bakery

"A baker in a Boulaq Abu al Ela bakery

Money to buy bread at a bakery in Khan el Khalili

Bread selling kiosk in the Boulaq Abu al Ela area in the center of Cairo.

Bread selling kiosk in the Boulaq Abu al Ela area in the center of Cairo.

"Street food made of "foul" (beans)

Loaves of bread in front of a street vendor in downtown Cairo.

While most sources point to domestic corruption at the bakery level, opportunities for bribes or the siphoning off of government-subsidized production materials exist at each step of the process — from harvest to consumption. Local farmers are notorious for using subsidized agricultural land, pesticides and fertilizers intended for subsidized wheat production for other, more profitable crops, like oranges or other citrus plants. As wheat progresses from the fields to the mills, and then to silos, theft at each juncture results in shortages of the subsidized wheat even before the supply hits the bakeries. Since the market price of wheat far exceeds the subsidized price, underpaid government employees and poor transport workers make ends meet by selling the stolen government commodity on the black market and paying a minor bribe to a local official.

Egyptian Supplies Minister Khaled Hanafi proclaimed that, beginning in July 2014, his reforms would attack the “smuggling mafia” that has emerged surrounding the subsidized bread supply-chain. He believes that aggressive accountability measures (about which he gave no details), coupled with Egypt’s promising new smart-card system that targets the neediest of Egyptians, will create more efficiency in the pivotal government program, with the potential to cut government bread subsidies in half annually. Hanafi assumed his position as Supplies Minister in late February following his predecessor’s dismissal on allegations of corruption.

While sources acknowledge the existence of organized criminal activity surrounding the public wheat supply, much of the corruption throughout the supply chain is actually due to structural failures, like crude sanitation, inadequate transport, and shabby storage facilities, as well as unlivable wages and poverty among workers.

In the case of Haditha, she and her family have had enough. After she and her neighbors saw no improvements in the subsidy program following the 2011 ouster, last year she and several local women pooled their families’ bread demand together and hired a woman from the countryside to produce their daily bread.

“It is more expensive, and many people in Imbaba could not afford this arrangement,” explained Haditha. “But after all the problems, it was worth it.”

She went on to vividly describe a memory of a violent clash in her neighborhood bread line. During a shortage, in a desperate attempt to get bread, a woman’s clothes were ripped off when she cut in one of the infamous lines. When asked the date of this particular altercation, Haditha responded coolly, “last month.”