Young Egyptians aching for a better future are concerned about its past. The country’s antiquities, a source of pride and economic revenue, are under threat. Instability following the 2011 revolution have left them vulnerable to looting and mismanagement.

Satellite images of the Nile Valley and Delta reveal archeological sites plundered during the Arab Spring and global economic crisis that preceded it. But it is less obvious threats that worry preservationists: Government bureaucracy and negligence.

Ahmed Khairy, an archaeologist and fired government employee, says the Ministry of Antiquities has tarnished the value of Egypt’s cultural heritage, one of its biggest tourist attractions. He points to gross financial mismanagement and the destruction or disappearance of precious artefacts.

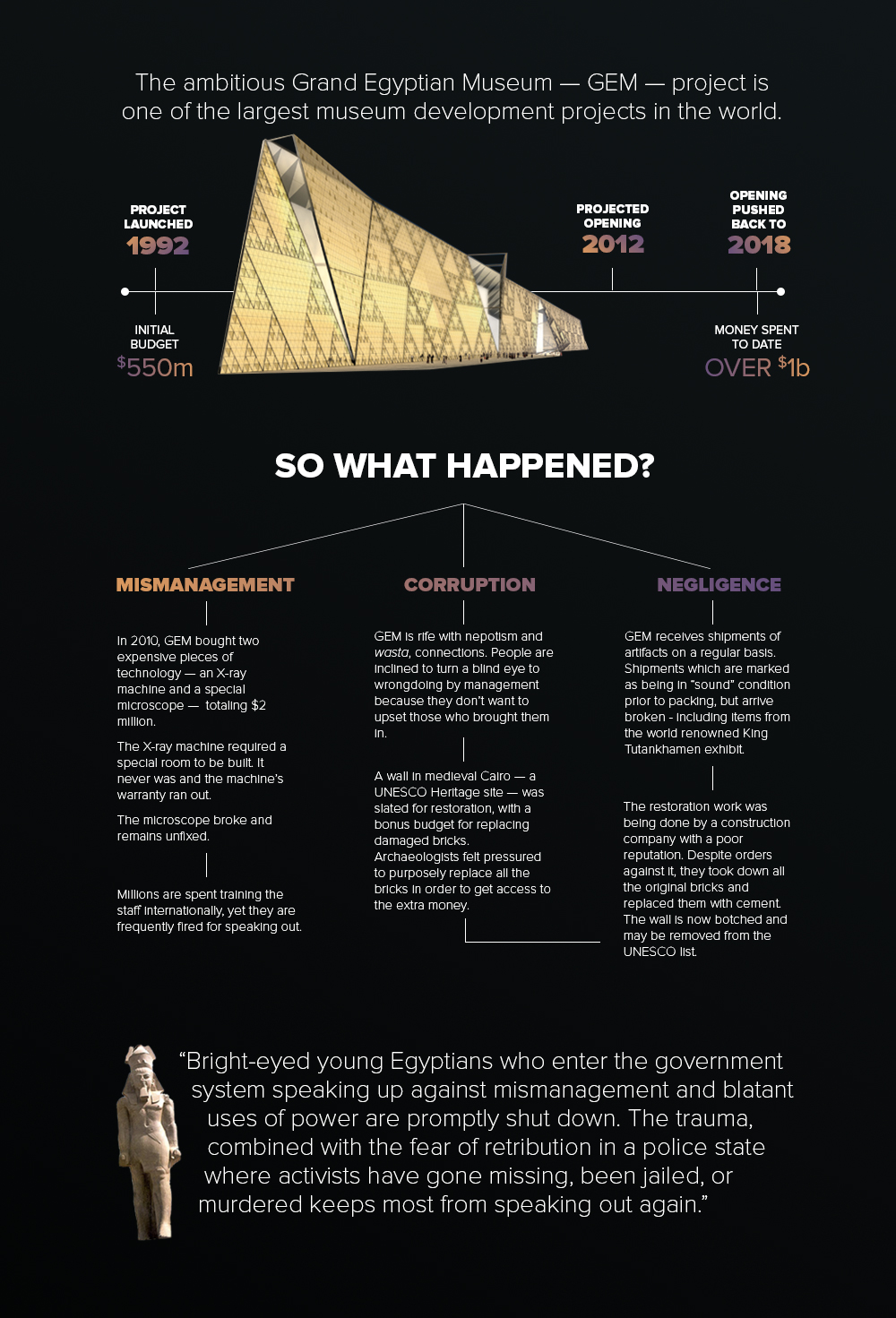

His view comes from a five-year stint working as a conservator for the long-planned Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM), which he considers a symbol of Egypt’s mismanagement. Once opened, GEM will be the largest archeological museum in the world. More than 100,000 artifacts, 3,500 of which belonged to King Tutankhamen, will be housed in the massive complex near the Giza Pyramid.

But spiraling costs and delays have left the public wondering if the museum will ever open.

The project launched in 2002, with a $500 million budget. Since then, costs have ballooned to more than $1 billion. The “soft-open” is delayed until 2018.

Former Minister of Antiquities Mohamed Ibrahim blamed GEM’s woes on the revolution, political changes and the weakness of the Egyptian pound against the dollar.

Khairy says MOA incompetence is a better explanation. He points to the ministry’s purchase and neglect of a $1 million scanning electron microscope and a nearly $1 million specialized X-ray machine designed to analyze antiquities.

He says the microscope was broken and never repaired in the five years he spent at GEM, despite repeated reminders to his superiors. And the X-ray, he says, essentially collected dust because it can only operate in a radiation-safe room, and that was never built.

“It would have only taken a month to build–why did they let [so much time] go by?” Khairy asks. “We need the device — it is very important for our work.”

Tawfik also told Al-Monitor the once-broken microscope is now fixed.

The same can not be said for many of Egypt’s precious antiquities. As a conservator, Khairy says he received shipments of artifacts twice a week, opening boxes and writing reports on their condition.

He says he opened several shipments reported in “sound” condition prior to packing, only to find them broken upon arrival at the museum because of improper packaging, Among the casualties were items from the world-renowned King Tutankhamen exhibit.

Khairy says he tried to sound the alarm to officials, but “they refused to give me copies of the condition reports.” He accused the Ministry of Antiquities of orchestrating a cover-up.

The conservator is not alone in his concern. After discovering damage to the golden burial mask of King Tutankhamen last year, a group of Egyptian archaeologists announced plans to file charges against officials at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. One even accused Antiquities Minister Mamdouh el-Damaty of lying when he denied news reports the mask had been damaged.

Khairy knew the ministry’s older generation would bristle over criticism from younger archaeologists, but he was undeterred from speaking out.

“I didn’t think they would fire me,” he says.

He was wrong.

GEM fired Khairy in February 2015. Ayman Badawy, director of GEM’s security and police, filed a complaint accusing Khairy of being the equivalent of a terrorist. It said the conservator incited GEM staff to strike over salaries and spoke impolitely to authorities.

“They said that I’m dangerous, that I threatened the security of the GEM,” remembers Khairy, who was the leader of an informal union of archaeologists.

He acknowledges he got in a heated argument with his supervisor, Tarek Tawfik, and joined colleagues in a protest over rumored salary cuts. But he says he was fired for trying to to uncover GEM and MOA negligence and corruption, which he says stem from low pay and nepotism.

“Everything works via ‘wasta’ (connections). Everyone stays silent because they don’t want to upset the people who brought them in,” he says, adding he had nothing to fear because he was hired through a rigorous application process.

Moreover, Ahmed says, the deep-rooted culture of corruption has extended to GEM. “GEM is known to everyone as “tikaya,” an Arabic word for an extravagant ancient building where you can find food and drink everywhere for free but nobody does any work. It’s a place where you can steal from easily.”

“GEM is known to everyone as “tikaya,” an Arabic word for an extravagant, ancient building where you can find food and drink everywhere for free but nobody does any work. It’s a place where you can steal from easily.”

The MOA and Tawfik did not respond to requests for comment about Khairy’s allegations.

Antiquities Minister Mamdouh el-Damaty told TEN TV in February 2015 that some numbers of Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated employees were to be cleaned out of his shop. The minister did not specify how many. Khairy says he was among at least 40 young archaeologists fired or reassigned from GEM.

The Egyptian government outlawed the Muslim Brotherhood and killed many of its supporters after the military overthrew Islamist president Mohamed Morsi in 2013. Referring to someone as Muslim Brotherhood is the equivalent of calling them a terrorist in Egypt.

“THEY CHOSE ME BECAUSE THEY WANT TO SACRIFICE ME — BECAUSE THEY DON’T WANT OUR COLLEAGUES TO MAKE NOISE.”

“Moving these people away is a big corruption because these people were trained very well,” Khairy says. “The staff is very unique. We have people sent to Japan, Germany, the U.S., and it costs millions of dollars to train us. All of that money went to waste because these people now work in places where they can’t use their skills.”

The advisory group will have its work cut out for it. In 2010, the year before the overthrow of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarek, tourism brought in a record $12.5 billion. Since then, revenues have plummeted, hitting just $7.3 billion last year. Officials blame a security vacuum and fearful tourists for the downturn.

Archaeologists say they’re fearful, too, but about the integrity of Egypt’s most precious treasures. In December 2015, four archaeologist were fired after complaining about lapses in MOA quality control in the renovation of a medieval wall in Historic Cairo, one of the world’s oldest Islamic cities. Hana Dlewati, whose name has been changed to protect her identity while her court case is pending, says she and her colleagues refused to acquiesce to pressure to carry out unnecessary fixes on the wall.

“The overseeing committee kept pressuring us to replace all the bricks so they could have access to this extra money” from a multi-million-dollar contingency budget, says Dlewati. “There are two problems with that: One, it’s destroying the historical information contained in the old bricks. And two, the extra money benefits those people, not the heritage.”

She says the ancient bricks were in good condition and could have been restored properly with some light cleaning. Instead, they were removed completely and replaced with new bricks of different dimensions.

THIS IS WRONG — NOBODY USES CEMENT IN RESTORATION!

“They used cement in the restoration, which is archaeologically wrong,” Dlewati says. “I’m very worried it will be removed from the list [of UNESCO World Heritage Sites] because of the botched restoration.”

She says her team reported their concerns multiple times to the head of the MOA project, as well as to the Ministry of Housing, but she says they were told to “let it go.”

That’s when they began carefully documenting the alleged violations they witnessed. Dlewati says they have hundreds of photos of the botched restoration and workers hacking at the wall with unsanctioned tools like axes and poles.

“The historical significance and integrity of the wall has been completely lost,” she says.

Moshira Moussa, an MOA media relations officer, tells another story. She says Dlewati and her colleagues made up the complaints because they did not want to work long hours and were upset about being moved to another project.

Mohamed Abdel-Aziz, head of the Historic Cairo Restoration Project and assistant minister of antiquities for the Islamic and Coptic unit, also vehemently denied the allegations.

“All those claims are lies; even the pictures they took do not prove anything,” he told Egyptian news outlet Ahram Online. “Yes, we use cement for supporting columns, but 50 metres away from the ancient wall.”

He called Dlewati and her team “young, angry, and incompetent.”