Liberalisation of the entry rules has turned this South American nation into a key transit country for trans-Atlantic migrants.

Murtada Al-Ridha, 20, gives an interview inside his family home in Quito, Ecuador, on 16 June of 2017. Murtada and his family sold everything they had in Iraq to start a new life far from the violence. (Photo by Mauro Pimentel)

The brothers Ahmed Al-Ridha and Mujtba Al-Ridha, 21 and 10 years old inside their home in Quito, Ecuador, on 15 June of 2017. They arrived on 24 of March with their mother and two other brothers. They tried to come in 2016 but a travel agent gave them fake travel documents. (Photo by Mauro Pimentel)

From left to right, Mujtba Al-Ridha, 10, Shah Al-Ridha, 19, Mujtba Al-Ridha, 10 and Alyaa Al-Safi, 44, inside their home in Quito, Ecuador, on 15 Jun of 2017. (Photo by Mauro Pimentel)

In a recent tour of Quito, 100Reporters and J4T heard the stories of:

- A Syrian mother of three who had fled the war, whose husband remained, working for the regime of President Bashar al-Assad. She wanted to take her children to the U.S., but was denied a visa

- A law graduate from Cameroon who has settled in Ecuador after her Canadian visa was denied

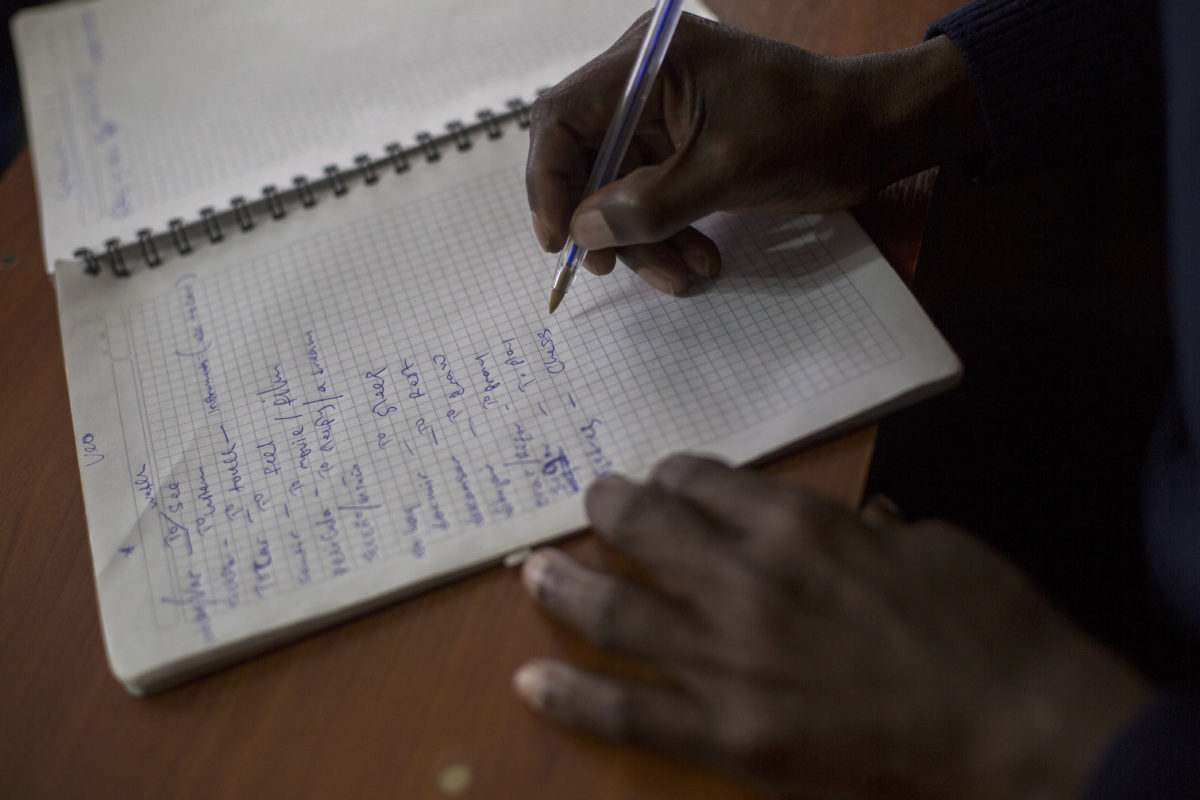

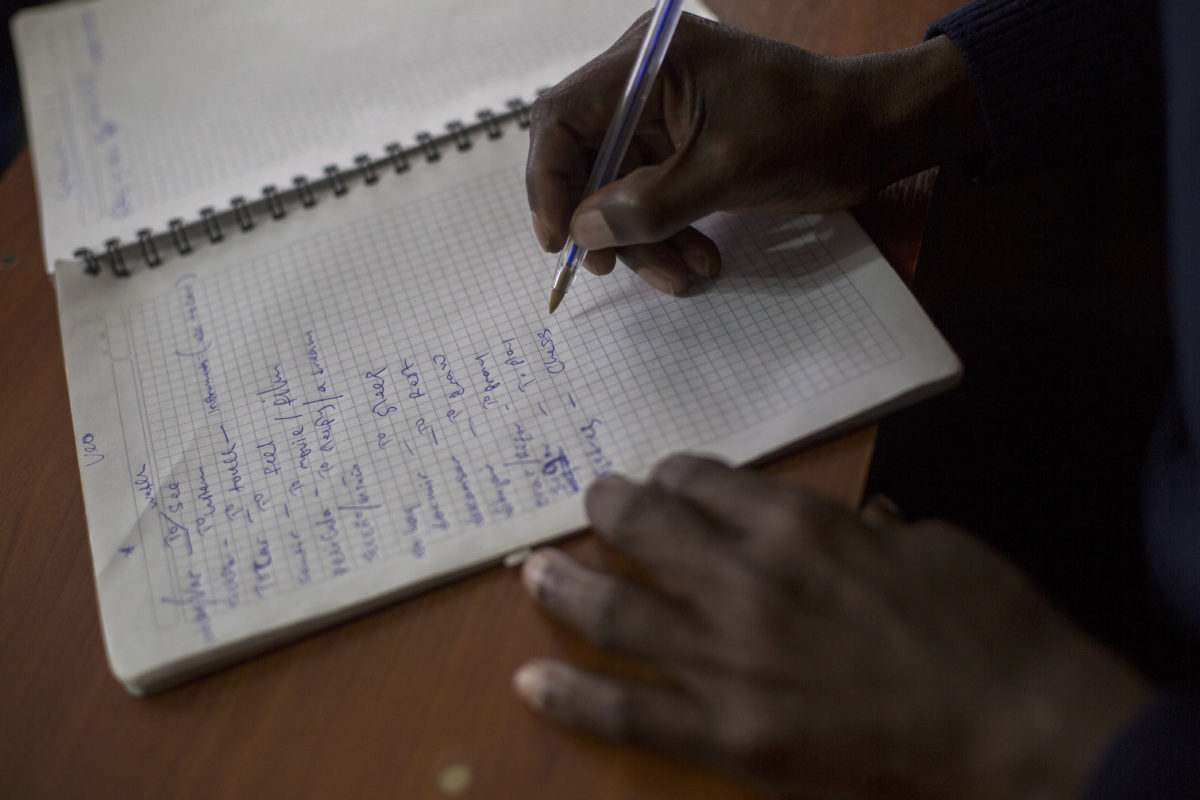

- A Nigerian teacher who wants to go to the US, but has spent five years being rejected by the US asylum and immigration authorities

- An Iraqi family that had to pay for the journey to Ecuador twice after they were tricked by travel agent who took their money

- A migrant from Sri Lanka escaping religious violence and is now looking to work, to send money back to his struggling family

- A former Afghan police officer who worked for decades on counter-terrorism, but had to flee when an attacker tried to throw acid at one of his children

- A 21-year-old student from Cameroon who has come to Ecuador to study. She says many people from her country flee north to try and reach Europe because “they say you have to risk things in life. In Africa in general there’s nothing. They think in other places they will find things, to help the family back home.”

- A 29-year-old from Cameroon who chose Ecuador because he would not need a visa. “If I was to go to Australia or Canada it would be so difficult.” His ticket cost $2,500, which he borrowed after “pleading with my mum to help me. My parents are farmers so went out to borrow money to pay my ticket to come here. Even now they are in debt. I was thinking coming here I could get something to repay these debts but up to now I’m jobless.”

- An artist who left Syria because of the war, and who is claiming asylum in Ecuador. He has other family members in Europe, but was unable to get a visa there

Chima Okoroafor, 35, an immigrant from Nigeria, leaving the African restaurant that has become a meeting point for Africans in Quito, Ecuador, on 13 June of 2017. Okoroafor speaks seven languages. (Photo by Mauro Pimentel)

Imma Ezeiba, nigerian immigrant, talks with Ecuadorian neighbors in front of her restaurant in Quito, Ecuador, on 13 June of 2017. Imma sells Cameroonian, Nigerian and Ghanaian food in the restaurant opened one year ago. She's living in Ecuador the last five years. Her brother lives here before so she decided to join him. (Photo by Mauro Pimentel)

The hands of an Nigerian immigrant, during his spanish lessons at Asylum Access House in Quito, Ecuador, on 15 June of 2017. He's a teacher who wants to go to the US, but has spent five years being rejected by the US asylum and immigration authorities. (Photo by Mauro Pimentel)

Immigrants playing music during Father's Day service at the Pentecostal "Redeemed Christian Church of God" in downtown Quito, Ecuador, on 18 June of 2017. Peter Rotimi Oye, a Nigerian pastor and english teacher, Peter and his family have settled in Ecuador. They split the service between English and Spanish speakers.

Ibitemi Oye, a Nigerian pastor, take cares of the children during the Father's Day service at the Pentecostal "Redeemed Christian Church of God" in downtown Quito, Ecuador, on 18 June of 2017.

Peter Rotimi Oye, Nigerian pastor and English teacher, painting in his living room in Quito, Ecuador, on 17 June of 2017. Peter and his family have settled in Ecuador. The family is not following the trend of staying a few years, saving money, then and following the route to the North America. (Photo by Mauro Pimentel)

“Ask anyone and they would like to go to Canada. Or Europe is beautiful. But it’s just a dream… I know about people going Brazil to Quito to the US. Everyone thinks of US money, the passport, but you arrive to America and then what? Two days later you watch the news and America is sending 1,400 Iraqis home.”

Ali Al-Ridha

Ali Al-Ridha knew it was time to flee Iraq when the local Shia militia started asking friends and family about him.

They had found out he’d lost his faith. If they found him, he feared he’d be beheaded. So he fled, not even pausing to pack his things.

He travelled to Moscow, where he went online and looked up “countries that accept Arabic Muslims without a visa.” His best option turned out to be Ecuador.

Like that of other migrants on this new westward migration, across the Atlantic, Al-Ridha’s route was circuitous. Some tell of journeys through as many as six countries: from West Africa or Afghanistan to Turkey or Dubai, through Brazil, crisscrossing continents to reach the Americas. Al-Ridha flew first almost 2,000 miles north to Russia, then more than 9,000 west to Havana, Cuba. From there, he took a plane to Ecuador’s capital city, Quito, where he entered on a tourist visa before claiming asylum.

With the crisis in the Mediterranean showing no sign of letting up and 2016 the deadliest year for crossings on record, a number of economic migrants and asylum seekers are looking for new escape routes from misery. Instead of paying thousands of dollars to be smuggled to Europe on an unseaworthy dinghy, they fly to Latin America. Some then embark on a perilous path north through the Colombian jungle and crime-ravaged Central America, bound for the United States and Canada.

In 2008, Ecuador passed a new constitution that created an “open door” policy for all foreign visitors. From one day to the next, no-one needed a visa to enter, turning Ecuador from a little-known dot on the South American map to a key destination for people who wanted to travel to or through the Americas.

Although visa requirements were soon reinstated for some countries (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, Somalia) Ecuador maintains some the world’s most liberal visa standards.

Giovanna Tipán Barrera, director of the human mobility department of the Pichincha region that incorporates Quito, said so many “extra-continental” migrants have arrived in recent years that they are now running Spanish classes for Arabic speakers and other communities.

Her department has worked with migrants from Afghanistan, Syria, Congo, Ghana, and Iran, and while some arrive with nothing, others are “middle, middle upper class. They have the resources to pay for the journey, they do not want to take the boat” to Europe.

Although some of the people they work with will stay in Ecuador, others “use Ecuador as a trampoline to reach the US.” That concerns her, as the America’s passage can be as perilous as an improvised Mediterranean boat crossing: trekking through Colombia’s Darien Gap jungle is “suicide,” she said. Crime and guerrilla groups extort migrants. The fees to go north are considerable: $10,000 to $20,000 to travel from Ecuador to the U.S., by land.

Murtada Al-Ridha, 20, gives an interview inside his family home in Quito, Ecuador, on 16 June of 2017. Murtada and his family sold everything they had in Iraq to start a new life far from the violence. (Photo by Mauro Pimentel)

The brothers Ahmed Al-Ridha and Mujtba Al-Ridha, 21 and 10 years old inside their home in Quito, Ecuador, on 15 June of 2017. They arrived on 24 of March with their mother and two other brothers. They tried to come in 2016 but a travel agent gave them fake travel documents. (Photo by Mauro Pimentel)

From left to right, Mujtba Al-Ridha, 10, Shah Al-Ridha, 19, Mujtba Al-Ridha, 10 and Alyaa Al-Safi, 44, inside their home in Quito, Ecuador, on 15 Jun of 2017. (Photo by Mauro Pimentel)

Dr. Thania Moreno Romero, chief prosecutor for the Pichincha region, says there has always been a migration route from Ecuador to the U.S. and Canada. In the past, however, that migration was “a local phenomenon.”

“But since 2008 when we introduced freedom of movement, we have started to see people from Pakistan, from India, Afghanistan coming to our country,” she added.

Travelling between Ecuador and Colombia can be an easy walk; there are as many as 33 informal crossing points. Coyotes — a well-connected network of multi-national smugglers – are highly flexible and just change routes and vehicles when law enforcement manages to disrupt business.

Mauricio Burbano, deputy director at the Jesuits Migrant Mission in Quito and a professor at Ecuador’s Pontificia Universidad Catolica identified a recent increase in asylum claims from Syria and some African countries. He even tells the cautionary tale of a traveler from Equatorial Guinea who was told by smugglers he was being taken to France but ended up in Ecuador.

Juan Pablo Terminiello, a United Nations refugee official in Quito, said that while non-Latinos make up a very small proportion of the refugees claiming asylum in Ecuador (Colombians make up around 90-percent), migrants from other nationalities have started to appear with greater frequency.

“In the last two or three years the case-load has been changing. New nationalities started to appear in small numbers, from Asia, Bangladesh, from the Middle East – from Afghanistan, Syria, and from West Africa,” Terminiello said.

“Many of these countries are places that in most parts of the world they will ask for a visa, but here, they don’t,” Terminiello added. “Every day things are more restricted in most of the world, but Ecuador does not ask for this type of visa from a multiplicity of nationalities.”

Mughni Sief, 30, artist who left Syria because of the war pose for a portrait inside the house shared with another Syrian refugee in Quito, Ecuador, on 16 June of 2017. Sief is claiming asylum in Ecuador. He has family members in Europe but was unable to get a visa. For more on Sief, see Voices from Ecuador. (Photo by Mauro Pimentel)

In a recent tour of Quito, 100Reporters and J4T heard the stories of:

- A Syrian mother of three who had fled the war, whose husband remained, working for the regime of President Bashar al-Assad. She wanted to take her children to the U.S., but was denied a visa

- A law graduate from Cameroon who has settled in Ecuador after her Canadian visa was denied

- A Nigerian teacher who wants to go to the US, but has spent five years being rejected by the US asylum and immigration authorities

- An Iraqi family that had to pay for the journey to Ecuador twice after they were tricked by travel agent who took their money

- A migrant from Sri Lanka escaping religious violence and is now looking to work, to send money back to his struggling family

- A former Afghan police officer who worked for decades on counter-terrorism, but had to flee when an attacker tried to throw acid at one of his children

- A 21-year-old student from Cameroon who has come to Ecuador to study. She says many people from her country flee north to try and reach Europe because “they say you have to risk things in life. In Africa in general there’s nothing. They think in other places they will find things, to help the family back home.”

- A 29-year-old from Cameroon who chose Ecuador because he would not need a visa. “If I was to go to Australia or Canada it would be so difficult.” His ticket cost $2,500, which he borrowed after “pleading with my mum to help me. My parents are farmers so went out to borrow money to pay my ticket to come here. Even now they are in debt. I was thinking coming here I could get something to repay these debts but up to now I’m jobless.”

- An artist who left Syria because of the war, and who is claiming asylum in Ecuador. He has other family members in Europe, but was unable to get a visa there

Chima Okoroafor, 35, an immigrant from Nigeria, leaving the African restaurant that has become a meeting point for Africans in Quito, Ecuador, on 13 June of 2017. Okoroafor speaks seven languages. (Photo by Mauro Pimentel)

Imma Ezeiba, nigerian immigrant, talks with Ecuadorian neighbors in front of her restaurant in Quito, Ecuador, on 13 June of 2017. Imma sells Cameroonian, Nigerian and Ghanaian food in the restaurant opened one year ago. She's living in Ecuador the last five years. Her brother lives here before so she decided to join him. (Photo by Mauro Pimentel)

The hands of an Nigerian immigrant, during his spanish lessons at Asylum Access House in Quito, Ecuador, on 15 June of 2017. He's a teacher who wants to go to the US, but has spent five years being rejected by the US asylum and immigration authorities. (Photo by Mauro Pimentel)

Immigrants playing music during Father's Day service at the Pentecostal "Redeemed Christian Church of God" in downtown Quito, Ecuador, on 18 June of 2017. Peter Rotimi Oye, a Nigerian pastor and english teacher, Peter and his family have settled in Ecuador. They split the service between English and Spanish speakers.

Ibitemi Oye, a Nigerian pastor, take cares of the children during the Father's Day service at the Pentecostal "Redeemed Christian Church of God" in downtown Quito, Ecuador, on 18 June of 2017.

Peter Rotimi Oye, Nigerian pastor and English teacher, painting in his living room in Quito, Ecuador, on 17 June of 2017. Peter and his family have settled in Ecuador. The family is not following the trend of staying a few years, saving money, then and following the route to the North America. (Photo by Mauro Pimentel)

The Smugglers

For many on the road north from Ecuador, the path is challenge. For others it’s opportunity.

Oye Rotimi Peter, a Nigerian pastor and English teacher, has been in Ecuador for a number of years but says many of his congregation from Nigeria, Cameroon, Ghana, and Haiti are just “passing through.”

“They come to Ecuador for say one year, two years, get some money for the next ticket and they go. Most of them to North America or Canada,” he said.

Al-Ridha, who had three businesses back in Iraq but who was forced to abandon his home, said if you hang out in the right cafes in central Quito it won’t take long for you to find someone who’ll help ferry you north.

“I met someone in this cafe once, he said ‘do you want to go to America?’ he said he would take me and my daughter for $9,000. This was a Palestinian with a document from Syria. But the problem is not the money but the way. If you have a daughter – mine is now 19 – that’s a problem.”

He recalls that a friend from Sudan disappeared suddenly one day with two children, aged six or seven, attempting to reach the U.S. via Colombia. They made it, Al-Ridha said, although the father is in a U.S. immigration detention center.

“It’s very, very dangerous. He went without telling me,” Al-Ridha said.

Smugglers on this journey can be protection, or a threat.

They advise migrants on the best routes to take and the most helpful people. Hermel Mendoza of the Scalabrini Mission compares it to a “transnational business” that brings huge profits.

“Gangs had experience of transiting people – in the past from Ecuador to Europe and Africa. From there they started to build a network of traffickers from all these countries. Those same networks are now used by the coyotes to bring people here,” Mendoza said.

What was once like a service – guiding people on the northward trek – is now a “broader transnational smuggling network,” said Soledad Alvarez, an academic who writes about Coyoterismo and Ecuador’s position in international human trafficking.

“With so many controls, coyotes work as in a relay race: from here to Colombia, one coyote, then another and it goes on,” she wrote in a recent paper. “Via mobile phones, Ecuadorean coyotes are connected with foreign coyotes along the route. They exchange information and coordinate payments via Western union or Money Gram for the different stretches of the route.”

Moreno, the Ecuadoran prosecutor whose office is targeting organized crime and people traffickers, says that for smugglers used to carrying contraband the smuggling of a human cargo is “just another phenomenon for them.” For migrants, however, it’s also another layer of risk.

“These people are shut up in hostels. Their ideal is just to arrive in the US, but [once on the road] they become more vulnerable and more dependent on the traffickers. They don’t know the language, the customs. They are fooled into thinking the trafficker is protecting them and they don’t want to give them up. And the person they are in with knows their family – this the way in which they have power over their victims,” Moreno said.

Until recently a large operation in Bolivia provided false documents for a fee – principally Bolivian and Venezuelan passports that would make travel through South America easier for non-continentals. Moreno said there is also more evidence of fake documents made in Brazil.

The UN’s Terminiello said “illicit traffickers are working in the region, using these routes,” and his concern is that smuggling gangs could even be trying to abuse the asylum system to buy people more time.

The impact of this trade in people has also been felt north of the border, in Colombia. In August, 2016 a bus filled with migrants from Congo and Angola was stopped travelling from Cali, in the south of the country, to Medellin. Earlier that year, the Colombian navy rescued 53 migrants from Somalia, Mali, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Haiti and Cuba whose boat was sinking as they attempted to reach land near the border with Panama. In 2016, Colombian migration authorities deported 3,700 migrants with irregular papers from Colombia’s northern border port of Turbo.

The U.S. State Department’s 2017 Trafficking in Persons Report says operations carried out by officials in Ecuador against human smugglers is on the increase: from a low of 10 in 2014, to 52 in 2016, resulting in 56 arrests. Trafficking convictions are also rising, from 20 in 2014, to 40 last year.

Tracking smugglers is a never-ending job: when one route or operation is shut down, experts say, another jungle path opens up, run by a rival. And the complicated relationship between migrant and smuggler, consumer and provider, victim and offender, means very few ever offer up sufficient testimony to lead to a conviction.

“Trafficking operations are very organized,” says Dr Ernesto Pazmiño, Ecuador’s chief public defender. “They can have a relationship with the victims and get into contact with their families. They don’t say who they are, who is behind it. That makes it a lot more complicated.”

He places blame at Europe’s door: “It is evidence of the restrictions European countries put in place that people that want to go to the US find other routes, principally through Latin America,” he says. “So the increase in people trafficking is due to the migration policies of rich countries. More borders leads to more illegal crossings, people have to pay more money. These are human beings, but countries close their doors for people to move freely.”

“Ask anyone and they would like to go to Canada. Or Europe is beautiful. But it’s just a dream… I know about people going Brazil to Quito to the US. Everyone thinks of US money, the passport, but you arrive to America and then what? Two days later you watch the news and America is sending 1,400 Iraqis home.”

Ali Al-Ridha

Sanctuary, in Ecuador

Al-Ridha’s wife and his four sons have now been able to join him in Ecuador – they fled after one of his children was roughed up by police and then suffered a broken leg, struck by an assailant on a motorbike. His youngest child, Mujtba, 10, has learned “sí” and “no,” and has made a local friend. His daughter, who made the journey with him when he fled Iraq, loves the music, and hopes to go to law school to train as a lawyer fighting for women’s rights.

The family currently lives in a cozy, but cramped, house in the hills above central Quito, the only furniture in the wood-paneled living room a plastic table and chairs. “I lose my job, I lose my home, I lose my car. For a time I lost my family. I lost everything in my country,” says Al-Ridha.

At least for now, in Ecuador Al-Ridha says the family is safe.

On one of the walls is an oil painting inherited from the last tenants: a pastoral scene of snowy mountains that could be Switzerland or Canada. “I like it,” he says, of the painting, adding that it makes him feel peaceful. Might he have preferred to end up somewhere like that?

“Ask anyone and they would like to go to Canada. Or Europe is beautiful. But it’s just a dream,” he says. “I know about people going Brazil to Quito to the US. Everyone thinks of US money, the passport, but you arrive to America and then what? Two days later you watch the news and America is sending 1,400 Iraqis home.”