After unprecedented numbers of fishermen were left jobless following the country’s recent permitting process, some are blaming a lack of transparency and possible corruption.

CAPE TOWN, South Africa—Roland Jacob Wichman was number 1,307 on the government’s list of fisherman not allowed to fish here this year.

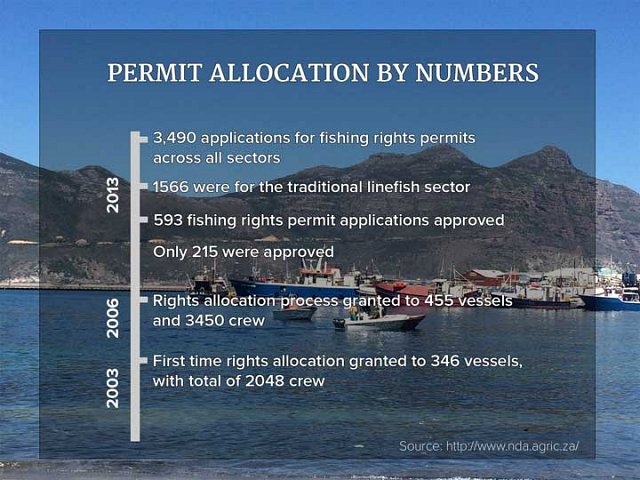

The 34-year-old, who has been fishing since he was a teenager, was among those left without a permit after South Africa’s Fishing Rights Allocation Process concluded late last year. As of January 1, names not on the list were not legally allowed to fish.

“I was an existing permit holder and then with the new process I had to apply again and I wasn’t successful,” says Wichman, who depends on the industry for his livelihood. “To get an answer that you’re not getting your right back is heartbreaking.”

Officials claim the permits were allocated under updated criteria that benefit the poor. But others have raised questions about the legality of the process, and cited possible corruption in the granting of permits.

Fighting back

The South African Commercial Linefish Association sought an urgent interdict against the allocation process in an attempt to find a solution for the thousands of fishermen, crew and hawkers who depend on the industry. Their concerns have been validated – partially. In May, Tina Joemat-Pettersson, the Fisheries Minister at the time, announced an independent legal audit found the fishing rights allocation process (FRAP) had “potentially fatal weaknesses” and would not stand up to a court challenge.

“To pre-empt further legal challenges, I intend to set aside the entire FRAP 2013 process, including all decisions and outcomes. I have directed that the requisite legal steps be initiated for this to happen,” Joemat-Pettersson said.

Fishermen allocated rights in the controversial permit process were allowed to exercise those rights, while former rights holders who lost their permits, like Wichman, were encouraged to apply for an exemption to continue fishing.

Origins of controversy

The new fishing permit allocation criteria were laid out in a 2013 amendment to the Marine Living Resources Act, first passed in 1998. The new bill’s stated intention is to protect marine life by regulating the fishing industry through permits and a quota system that limit the amount of fish caught—a move heralded by environmentalists, given the declining number of fish.

By making provision for small-scale fishermen, the amendment bill also intended to “transform the inequalities of the past fisheries system,” giving rights to those previously excluded from the commercial fishing rights allocation process in South Africa. In response, 100 permits were kept aside for new entrants.

But Commercial Linefish Association Chairman Wally Croome says that part of the legislation was misused. Of the approximately 300 traditional linefish permit holders operating last year, just over a third of that were awarded rights this year. It’s less than half of those allocated permits in 2005. And Croome says many of the 100 new entrants don’t meet the right criteria. He says many do not have a vessel to go out to sea, nor the experience to do so.

It’s not the first time then-Fisheries Minister Joemat-Pettersson and her department have been accused of questionable behavior. In December 2013, a report by the country’s Public Protector found “maladministration, improper and unethical conduct” during the department’s awarding of a multi-million dollar tender to manage the country’s fishery vessels.

According to the report, Joemat-Pettersson “acted recklessly and improperly.” The report recommended South African President Jacob Zuma take disciplinary action against the minister. He never did.

Joemat-Pettersson has repeatedly stressed the amendment fishing bill is aimed at restoring the dignity of poor traditional fishermen and women, and rectifying past prejudice.

Much of the outrage over the bill’s effects is coming from Hout Bay, a fishing town less than 30 minutes from Cape Town’s city center. Others are in smaller fishing villages along South Africa’s coast. They’re fishermen who go out to sea to make a living, selling their catch to the local market. In most instances, their fathers were fishermen, and often their grandfathers.

“We are a fishing community,” says Richard Guenantin, in Hout Bay. “We own nothing. We have no option but to take what is in the sea.”

While he says he understands why the permits are needed, Guenantin doesn’t agree with the process and criteria used to score applicants. For example, more points are given to applicants who have invested in vessels and equipment, and to those who provide temporary or permanent employment to the crew, along with medical and pension benefits. These are costly mandates, especially for the average fisherman.

“The department must give [permits] to everyone … bonafide fisherman, everyone who lives off the sea,” Guenantin says. “We’re not builders or carpenters or contractors, we are fishing people.”

Despite being granted an indefinite fishing exemption while legal matters are sorted, Wichman says he’s still worried.

“With the fuel I have left, I can go out and poach to try and make some of my money back, but we don’t want to do that,” he says. “We want to work [legally] on the water. We are fisherman, we don’t want to be part of the poaching scene … [or] chased around by police because we haven’t got our paperwork.”

Both the country’s official opposition party, the Democratic Alliance, and the Commercial Linefish Association say legality should be questioned in the permit allocation process. They jointly submitted an urgent Promotion of Access to Information Act application in early 2014, demanding reasons why some fishing rights applications were denied, and why some were awarded—specifically referring to those applicants who don’t seem to meet basic criteria.

The government has highlighted a commitment to transparency, noting that every applicant will receive a notification letter informing of the delegated authority’s decision together with the reason for that decision and an appeal form. That has not happened for many. The Democratic Alliance’s spokesperson on Fisheries, Pieter van Dalen, says he won’t stop putting pressure on the department until promises are kept. He has requested to see scoresheets to try to understand why some applicants were successful, and others not.

He agrees with claims that many who were awarded permits are not eligible. This, he says, suggests possible ties to the government.

“Some don’t even have boats,” he says.

Fishermen hoping to know their fate are partly a prisoner of politics. During a cabinet reshuffle, in late May, President Zuma redeployed Joemat-Pettersson to Minister of Energy—a move cast as a promotion. The former president of the influential National Union of Mineworkers, Senzeni Zokwana, was appointed to Fisheries Minister, while the country’s former police commissioner, Bheki Cele, who was fired in 2011 after being found guilty of maladministration, was made deputy minister.

In August, DAFF officials told Journalists for Transparency the new Minister has been briefed on the fishing rights internal audit by investigators. Director of Communication Services for Fisheries Lionel Adendorf says the minister is yet to make a decision on how to move forward with the permit process.

It’s both a welcome change and a worrying appointment for Wichman and other fishermen that insist the government needs drastic, transparent measures to ensure that those who depend on the industry for their livelihood can continue to work.

“Hopefully the government makes the proper decisions now. I just want to fish. I just want my right back,” Wichman says.