NAKIVALE, Uganda — Gratien Zimy Ntezimisi lives in a shelter as sturdy as a small castle. He says there’s a good reason he lives behind cement walls and an iron door with a heavy lock.

On some nights, he says, unseen figures attack his home. They throw stones that clatter on his metal roof and push and ram his door.

“They try and force the door to see is there a way for them to enter, fight and maybe kill me,” he said. “When they fail, they vandalize the compound, my trees, my vegetables.”

Even in daylight, the 41-year-old from the Democratic Republic of the Congo feels like a pariah. He says his neighbors in this 71-square-mile refugee camp near the Tanzanian border are reluctant to help him report problems to the police, or even to greet him.

“I am surrounded by neighbors, but when such things happen to my home not one of my neighbors have come to me to say they saw something.”

Ntezimisi says the trouble started three years ago, when he reported corruption involving staff members of the U.N’s refugee agency, UNHCR, to the agency directly.

He had been working as an interpreter for an organization contracted by the U.S. government, sitting in on interviews with refugees who were about to be resettled in the States — a job that made him well known in the settlement. Refugees began to approach him, confiding similar stories, about UNHCR staff members and suspected brokers asking them to pay to start a new life in the West.

“You keep on hearing the same story from different people on a regular basis,” he said in Kampala, Uganda’s capital, in July 2018, in the first of many interviews. Ntezimisi had traveled nearly 190 miles overnight to meet this reporter because he said he was desperate to publicize what was happening.

#embed-20190327-un-nakivale-map iframe {width: 1px;min-width: 100%}

var pymParent = new pym.Parent(’embed-20190327-un-nakivale-map’, ‘https://dataviz.nbcnews.com/projects/20190327-un-nakivale-map/index.html’, {});

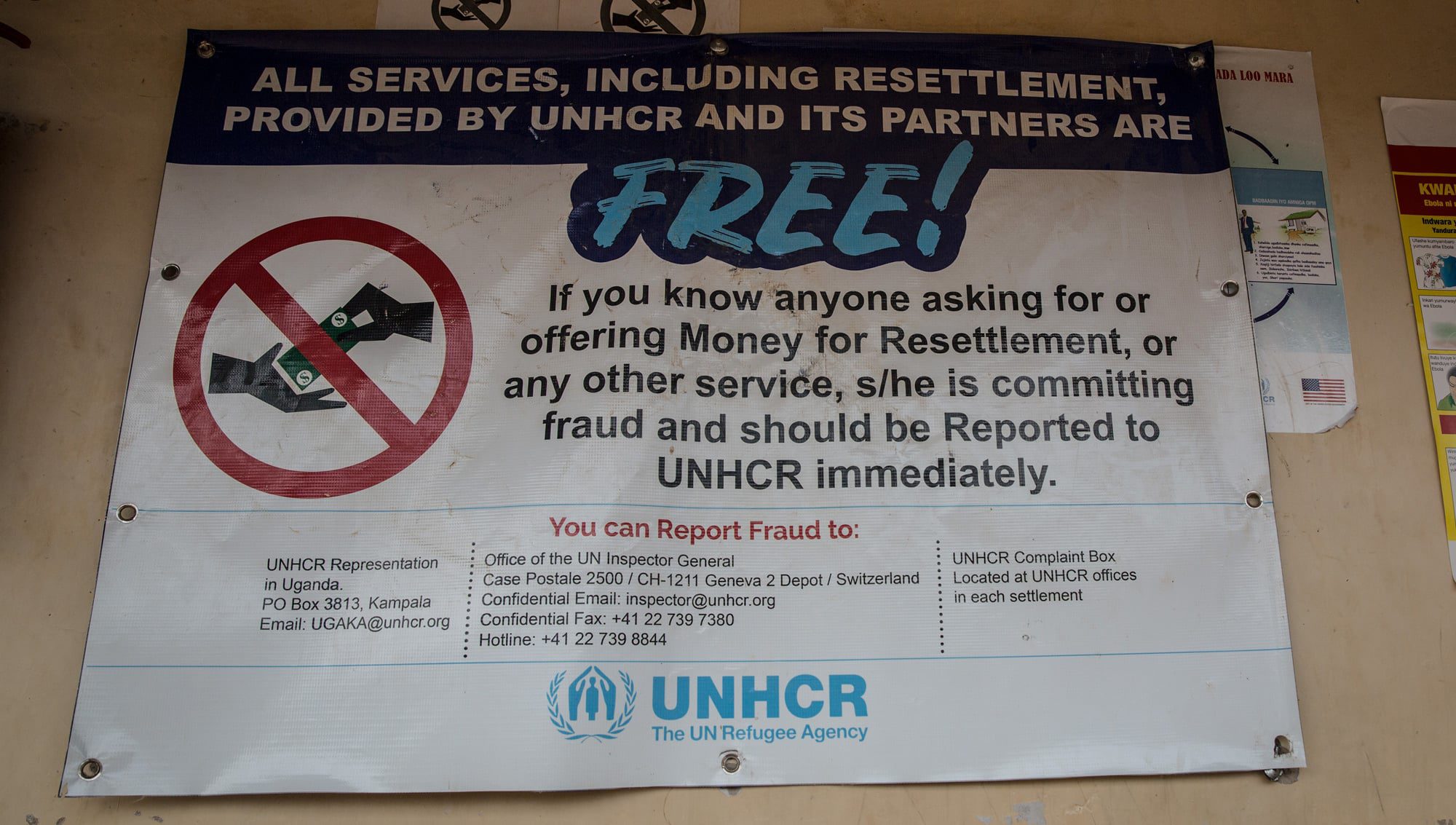

As part of his interpreting job, Ntezimisi had been trained in tackling fraud and corruption. All over Nakivale, as in many other refugee camps around the world, anti-corruption posters are ubiquitous, informing refugees that services are free and wrongdoing should be reported to UNHCR. So Ntezimisi decided to do just that.

On May 31, 2016, Ntezimisi travelled to UNHCR’s headquarters in Kampala with a report he had taken two months to compile, full of specific information about instances when refugees were asked for money. It named the offenders, the victims and the amounts, all carefully typed. The report implicated UNHCR staff, the police, other aid organizations and government employees.

“It should be noticed that the people mentioned in this current fraud report is just the tip of the iceberg,” he wrote in the document. “The problem is so massive that a poor refugee without any resources could hardly pretend to be able to uncover the whole scam network in its entirety.”

Posters and promises aside, Ntezimisi was unprepared for what happened next. While UNHCR instituted a formal investigation, the interpreter says he saw nothing change, and instead became the target of ongoing retaliation for speaking up.

His experience was hardly unusual. In a seven-month investigation across five countries with significant refugee populations, more than 50 refugees, current and former UNHCR staff members and former U.N. investigators accused UNHCR of failing to adequately address corruption allegations, failing to protect refugee whistleblowers, and “whitewashing” investigations so as not to lose support from donors. This follows similar claims by refugees in Sudan last year.

Refugee whistleblowers in Kenya, Uganda and Yemen accuse UNHCR of encouraging them to report allegations, but then failing to properly protect them when they do. (Only refugees who explicitly agreed to be named are identified; all others are kept anonymous because of the risk to their safety.)

Retaliation allegedly suffered by refugees who speak out has included physical violence, withholding of food rations, changes in their refugee status, sudden obstacles to receiving UNHCR assistance, death threats and arrest.

Refugees interviewed in Kenya, Yemen, and Uganda accuse UNHCR staff of calling the police on them after they protested against corruption, resulting at times in arrest or assault. Refugees in Uganda reported spending days in a police cell, while Sudanese refugees in Libya accused UNHCR staff of assaulting them after they tried to protest corruption in Tripoli late last year.

Though the UNHCR can and does launch fraud investigations through its internal Inspector General’s Office (IGO), victims, staff, former U.N. investigators, and lawyers say that the IGO lacks the mandate to protect refugee witnesses.

Click here to read NBC News and 100Reporters versions of this story.

Former UNHCR and U.N. investigators, as well as others with experience of U.N. processes, also argue that diplomatic immunity allows U.N. staff to exploit refugees without fear of punishment. “There has been a bit of movement, but it’s moving the deck chairs on the Titanic. You’ll never get accountability with them policing themselves,” said Edward Flaherty, a Geneva-based lawyer who’s worked on U.N.-related cases for two decades.

“The U.N. fiddles around the edges, they issue new policies, [but] the immunity and impunity remains. The lack of accountability remains…It’s amazing that [corruption] is still being revealed, because the U.N. crushes whistleblowers.”

In an emailed response to written questions, UNHCR said immunities are given “in the interest of the organization, not for the personal benefit of staff.”

“UNHCR cooperates in the administration of justice. Where a matter has been referred to national authorities for criminal accountability, waivers of immunity are facilitated through United Nations Headquarters in New York,” said UNHCR spokesperson Cecile Pouilly.

In the past, UNHCR has pointed at its lack of witness protection. “Lessons learned from key investigations,” as listed in a March 2018 overview of the IGO’s work, noted that “the support that UNHCR can provide to witnesses who face security risks when they are involved in investigations is limited” and “the primary responsibility for witness protection lies with the host State.”

Speaking in an interview at the United Nations General Assembly last September, UNHCR Deputy High Commissioner Kelly Clements said, “We’re a humanitarian agency. We’re not a law enforcement agency. … So there are limits to what we can do. … We often will rely on national authorities or local law enforcement authorities to help us.”

Pouilly said the agency recognizes it has a responsibility to protect those who come forward and cooperate with investigations. “While bearing in mind the primary responsibility of the host state in ensuring the physical security of refugees within its territory, UNHCR has devoted significant attention to strengthening measures to protect witnesses and persons of concern who cooperate with an IGO investigation, and these efforts are continuing.”

“Taking into account good practice in international and national investigation, the IGO takes steps to mitigate risks to witnesses during the investigation phase, including in the conduct of interviews, the anonymization of testimony and redaction of investigative findings and reports,” Pouilly said, adding that the IGO can request additional help for witnesses on a case-by-case basis, including organizing a security assessment, providing counseling, financial and legal support, and relocating refugees either within the country they’re in, or resettling them to another country.”

‘Maintain a low profile’

In two-and-a-half years of communication between Ntezimisi and UNHCR reviewed by this reporter, his pleas grew more and more desperate, as he transformed from moral whistleblower to hunted victim: refused food rations, intimidated by police and locked for days in a cell after he says UNHCR called security on him.

“Every time I’m in Nakivale I get threats, so I go to Kampala or Mbarara and report to UNHCR,” he said, referring to a local town. “They always take me back with the police.”

He added, “Reporting is basically a way for me to say I’m suffering. If I keep quiet, no one will know that I’m undergoing such mistreatment.”

In one November 2017 incident documented through emails, UNHCR asked Ntezimisi to visit Ugandan police for what they called a “discussion” about his safety. Instead, he says he was met by nine police officers, who first told him to finger the police involved in corruption, and then threatened him, accusing him of damaging the name of the police force and government.

On Nov. 24, 2017, Ntezimisi wrote to a UNHCR field officer, Henok Ochalla, telling him what happened and asking, “Is it logic[al] for me to rely on the Office of the Prime Minister and police for my physical protection?”

“Worse than all these,” he added, “is the UNHCR position, which is thinking that I am forging all these complaints of insecurity [to get] resettlement.”

Responding, Ochalla said he was “totally convinced” the meeting should have been about how to protect Ntezimisi, and said he would seek clarification, while advising Ntezimisi to “maintain [a] low profile.” However, Ntezimisi says he still never received any direct protection.

Earlier in 2017, says Ntezimisi, his name disappeared from the list of refugees allowed to receive food rations in his area. Ugandan officials then reissued Ntezimisi’s food ration card, he says, but it was a card he could only use in a remote village, meaning he could not collect his monthly allocation of food.

He wrote again to UNHCR’s Nakivale office in August 2018, saying he had gone 16 months without food aid “as punishment for reporting the fraud.” In response, UNHCR staff member Ghulam Nabi Seddiqi wrote, “I am sorry that the challenge could not be addressed. I will once again talk to concerned actors for advocacy purposes.”

“I have become a beggar to find a meal,” Ntezimisi messaged this reporter, sick with typhoid and going days without food. “That’s how I live, asking friends [for charity] for two years now.”

Asked about Ntezimisi’s case, UNHCR spokesperson Adrian Edwards said help was offered and refused. However, Ntezimisi says the only offer was to move him to another Ugandan refugee settlement, where he would still be at risk, because accused UNHCR employees move between settlements regularly.

The Ugandan Office of the Prime Minister did not respond to requests for comment.

Last June, Ntezimisi traveled back to the UNHCR Kampala office with five other witnesses of corruption to request protection again, but says the agency offered none. The refugees ended up sitting in front of a UNHCR vehicle in protest, refusing to move until someone helped them. In response, Ntezimisi and other participants say UNHCR called the police, who hauled them away.

“We spent three days, three nights in the police station here in Kampala,” Ntezimisi said. His account was confirmed by another refugee who was with him.

“We requested them to temporarily find a solution,” said Ntezimisi. “Rent a house here, identify who within our group (is) at the most high-risk level, put (us) in the house while (we) are waiting for a durable solution, either resettlement or other means.”

“They said no,” Ntezimisi said. Instead, “They started to intimidate us.”

Back when he first reported corruption, Ntezimisi says he had faith that something might come of his complaints. In November 2016, he testified to representatives from the UNHCR Inspector General’s Office, who came from Geneva to look into allegations, telling them both of exploitation he had heard about and of the pressure he had been put under since disclosing it.

Thirteen months later, on Dec. 12, 2017, Ntezimisi received an email from Coralie Colson of the IGO, who had also interviewed other refugees in Nakivale.

“As promised, I am getting back to you with respect to the allegations you have made against UNHCR staff,” she wrote. “The Inspector General’s Office has now concluded its investigation and has decided to close the case. This email hereby informs you of the IGO’s decision.”

He was given no explanation. “I think the reason Geneva concluded that nothing wrong was found is that the more the UNHCR name is clean, the more they will get funding and the benefit they get from that,” Ntezimisi said. He was upset, he said, but not surprised.

Questions emailed to Colson were responded to by Adrian Edwards, a UNHCR global spokesperson. Edwards said the probe was dropped because of “suspected interference with witnesses including possible coaching of them.” He did not confirm who may have interfered with the investigation, though he said Ntezimisi was the “main complainant.”

When asked about this, other refugees who gave evidence during the investigation said they didn’t even know Ntezimisi, but interference did happen after a local UNHCR staff member was given details of Colson’s interviews and called refugees to intimidate them in advance.

The success story that wasn’t

At the same time Ntezimisi made his initial report about corruption, UNHCR was enthusiastically promoting Uganda as one of the best places in the world to be a refugee. Spokespeople praised the country as a “model example,” citing Kampala’s policy of giving refugees a plot of land and rights that included freedom of movement. Media coverage in major outlets like the Guardian, BBC, The New York Times and Der Spiegel in 2014 to 2018 lauded Uganda as a rare positive refugee story.

Alongside the publicity came pushes for more funding from donor countries. In 2017, Uganda and UNHCR jointly announced they were looking for $8 billion to provide for South Sudanese refugees who were fleeing the civil war at home.

Ntezimisi and a dozen other refugees in Nakivale said they felt vindicated in February 2018 when corruption in Ugandan refugee camps at long last made headlines. In October 2018, the Ugandan government admitted refugee figures had been exaggerated by at least 300,000, while the U.N.’s Office of Internal Oversight Services (OIOS) ruled in a damning audit in November that UNHCR in Uganda critically mismanaged donor funds in multiple cases.

Over the past year, Ntezimisi says, UNHCR staff members in Nakivale have stopped denying corruption exists. Instead, they have begun to accuse him of “taking advantage” of the fraud to get resettlement.

No protection

Like most refugee camps, Nakivale is extremely remote. To reach it from Kampala takes six hours on a cramped bus, followed by nearly an hour in a taxi over bumpy, muddy roads. Many refugees never leave this isolated expanse of countryside. They live on the bare minimum. Some have waited 10 or 20 years to see if peace might come to their homelands, and they are desperate to escape.

Ntezimisi’s plight has served as a warning to others tempted to complain openly of corruption.

“It’s not the first time we spoke about this. We get repressed. Our files get blocked,” warned another Congolese refugee there. “The U.N. does not have any protection mechanism for whistleblowers. We’ll tell you things, but we have no guarantee.”

Among UNHCR staff, dissatisfaction about the lack of progress in tackling corruption is not uncommon. Staff say the IGO is both too far removed from the reality on the ground and not adequately independent to carry out its function.

A current UNHCR resettlement staff member, who spoke on condition of anonymity, described instead subtly trying to investigate other colleagues’ work, despite a lack of authority to do so. The staff member said suspicions surround certain employees, but only the Geneva-based IGO has the authority to investigate them. Local management, with better knowledge of the specific circumstances, tends to brush aside allegations, the staffer said.

Much of the problem, the staffer said, stems from a disconnect between international employees and the refugees they are ostensibly there to serve. Complaints may not be believed or even heard. “There’s definitely a culture of not wanting to be seen talking to a refugee, and, in a way, not treating a refugee as a person. You don’t want to be seen to be overly friendly to a refugee.”

Keeping one’s distance could be judged as fair, an effort to avoid favoritism, “but there’s a negative,” the staffer said. “You’re not seeing them as humans or taking them at face value.”

Still, the staff member wanted to remain anonymous. “I have a grand plan of fixing the problem from the inside out, however idealistic and unrealistic that is. Resettlement is a lifesaver for very few, so it really upsets me when the process is corrupted.”

According to U.N. figures, the Inspector General’s Office concluded 144 investigations in 2018, of which 49 percent were substantiated. From 2017 to 2018, an IGO report said, 897 complaints were received relating to misconduct, of which nearly half involved some kind of fraud.

“In 2018, additional investigators were recruited and some stationed in Nairobi, Pretoria and Bangkok enabling them to be deployed rapidly and to have a better understanding of local contexts and issues,” the U.N.’s Pouilly said.

In total, 10 staff members were dismissed on grounds of corruption from 2017 to 2018, she added. However, critics say without systemic overhaul, a few dismissals do little to change a culture of exploitation.

“It fits a pattern and is what I’d describe as commensurate with the culture of the U.N. in general,” said Peter Gallo, another former U.N. investigator, speaking about drawn-out investigations with limited conclusions.

Said Gallo, “The U.N. will always be happy with a result that has a lot of activity and ends with no result.”

A former UNHCR staff member, who quit after participating in an IGO investigation that came to nothing said that was the U.N.’s “typical strategy of covering up, containing damage.”

“It is really a headache for me when people pay less attention to human lives and care more about polished reports for donors and PR propaganda,” the ex-staff member said. “Bunch of liars.”

UNHCR guidance for employees emphasizes the importance of maintaining the image of an honorable organization. In a “brand book” released in April 2016, UNHCR said all staff communications with the media, partner organizations, governments and refugees should convey “the attributes that audiences universally say are most likely to make them want to support a humanitarian organization,” including “can be trusted.”

When asked whether UNHCR is whitewashing wrongdoing by staff to protect its public image, UNHCR spokesperson Pouilly responded: “We wish to stress that eradicating any misconduct from our organization is a key priority for UNHCR and we have extensively communicated on these issues, both internally and externally.

“As you know, our programs are only partially funded, which has a real impact on the lives of millions of refugees around the globe. Without additional financial support, we will not be in a position to offer to refugees the protection and assistance they desperately need.”

Death threats

In 2016, an IGO investigation was launched in Kakuma refugee camp, northwest Kenya, as a result of what refugees described as a rare anti-corruption campaign by a senior international UNHCR staff member, Inge De Langhe. More than 20 refugees interviewed there last October for this report said corruption had been a problem as long as they could remember.

Within months, though, De Langhe was forced to leave the camp as a result of death threats, according to seven refugees who knew her, as well as former UNHCR contractors and staff members. “She was chased like a wild animal,” said one Congolese refugee with knowledge of events. UNHCR Kakuma camp head, Tayyar Sukru Cansizoglu, told Journalists for Transparency he hadn’t heard of this, and believed De Langhe left when she reached the end of her contract.

Four UNHCR staff members in Kakuma were eventually referred to the Kenyan police, with at least one being arrested and two resigning. Refugees and former staff said the referral and resignations wouldn’t have happened without De Langhe’s persistence.

However, after De Langhe returned to UNHCR headquarters in Geneva, five refugees told me the incident had proved how alone they are: They felt both abandoned and retaliated against, while two reported being contacted by other UNHCR protection staff and warned not to communicate with any foreigners again.

“You used to communicate with the white people. You used to communicate with Inge, now your case has gone to Geneva with her,” one refugee said he was told by UNHCR staff member George Micheni, who was also accused by another refugee of asking for a $1,000 bribe and has since moved to work for UNHCR in Egypt.

When contacted on their UNHCR email addresses, both De Langhe and Micheni said they couldn’t comment, instead referring questions to UNHCR media spokespeople, who said they can’t disclose details about specific staff members.

Another refugee alleged Kenyan UNHCR staff began paying refugees to give false information to visiting investigators, claiming he was offered money, too, but turned it down.

Two refugee witnesses were eventually moved to Nairobi for their protection and disappeared from communication, but the fallout was much greater than that.

“Geneva [has] no power here,” a UNHCR contractor and refugee in his 20s said. “Things are worse now.”

For those left in the camp, the feeling of danger is very real. In several cases, witnesses said refugees were killed by police or members of the local community, seemingly without repercussions – though there is no proof these killings were linked to corruption.

The wife of one of those killed asked this reporter to make UNHCR aware that she needed protection. Despite UNHCR staff saying they would contact her, at the time of publication, five months later, the woman says she’s still heard nothing.

‘There is a cancer’

Five hundred miles away, in Nakivale, Ntezimisi is full of advice on how corruption could be curtailed, but becoming more despondent by the day. He suggests limiting the power of local employees, who may be under pressure from their families to find extra income. Increased transparency as to how the resettlement process works would also help, he said.

“Many people are kept in darkness. They don’t know what to expect, who expects what,” he said, adding that UNHCR “keeps it a secret, and people exploit that secrecy.”

Ntezimisi says donors should conduct their own investigations and speak to refugees directly to monitor what’s going on. “They keep pumping in money to the system which is corrupt, and the people are suffering without their knowledge. It doesn’t make sense.”

Ntezimisi also wants to reach out to other refugees in similar situations, maybe through a YouTube channel. He says he would like to offer help to anyone trying to change UNHCR’s systems, but thinks reform is unlikely in the short term, particularly if the messenger is the one who is punished.

“Unfortunately, I discovered that there is a cancer,” Ntezimisi said. “You’re not going to blame the doctor because he told you you have a cancer.

“That cancer needs to be treated.”

This report was produced in a collaboration between 100Reporters, a nonprofit investigative news organization, NBC News, and Journalists for Transparency, an initiative hosted by the International Anti-Corruption Conference Series and Transparency International.