Europe is cracking down on migration, but many of northern Africa’s most vulnerable feel it’s unsafe to stay still.

The Lonely Fight in Sudan: One Official Works To Stem Migrant Smuggling – Without A Car, A Photocopier Or Any Staff

Ismail Omer Teirab has worked as deputy chairman of Sudan’s National Committee to Combat Trafficking for the past two years. It’s a high-profile job, and he’s had to deal with a lot of the criticism associated with funding from the European Union for anti-smuggling initiatives.

Founded after the Human Trafficking Act of 2014, Teirab’s committee is mentioned again and again in discussions around the Khartoum Process, a dialogue between countries along the migration trails from North Africa to Europe. Under this initiative, the EU has given more than 200 million Euros to Sudan to stop the flow of migrants… (read more)

On The Rough Road in Sudan

It took two months for Helen to fully regain her memory after her first attempt to get into Libya.

The clarity of hindsight returned, and, in a cramped, unlit room in the Sudanese capital Khartoum, she sat slumped, her delicate features crumpling as she recounted a harrowing odyssey from her home country to the desert in the north. The 22-year-old Eritrean had set off in a group of 87 migrants, all eager to move on from the discrimination and exploitation they had experienced in Sudan. But now almost a third of them were dead or missing. “All of us lost our minds,” she said. “We couldn’t remember where we had been…” (read more)

An Eritrean teenager sits on his bed in the unaccompanied minors section of Shagarab refugee camp, eastern Sudan, on July 20, 2017. (Photo by Sally Hayden)

Boys sit in their dormitory in the unaccompanied minors section of Shagarab refugee camp in eastern Sudan, on July 20, 2017. (Photo by Sally Hayden)

A young girl stands in a dormitory in the unaccompanied minors section of Shagarab refugee camp, eastern Sudan, on July 20, 2017. (Photo by Sally Hayden)

Eritreans play pool in one of the makeshift pool halls in Shagarab camp in eastern Sudan, on July 20, 2017. (Photo by Sally Hayden)

Children walk to school in Shagarab camp in eastern Sudan, on July 20, 2017. (Photo by Sally Hayden)

Nurah suspected her 13-year-old son was dead when the smuggler who claimed to be holding him hostage refused to put him on the phone. That was three years ago, but the series of events still runs through her mind every day.

Her youngest had left home, without warning and leaving no good-bye note or clue on his destination. Nurah was already anxious because just a month before her older son had abandoned Sudan, hell-bent on making it to Libya and then across the Mediterranean Sea to Europe.

And then the angry man called, demanding a ransom of $2,000. “I said if my son was alive I wanted to hear his voice, but they didn’t put him on,” she recalls, hunched over in a hot, cramped room in Sudanese capital Khartoum, her eyes staring firmly at the tiled floor.

Today, Nurah is on her own. Like most Eritreans and Ethiopians in Sudan she describes herself as a habesha – a second-class citizen. She was working at one of the tea stalls dotted along the banks of the Nile river running through Khartoum, but unending harassment from locals and Sudanese security ended in two men following her home, kidnapping and raping her. Now she’s afraid to go outside.

Nurah’s story (she requested anonymity because she fears retribution from smugglers or Sudanese security) is just one in a thick book of woes about Sudan. Here, young people are disappearing with startling frequency – encouraged by smugglers to leave for Europe without telling their parents, who’ll be hit up later with a staggering bill for the passage.

Most Sudanese migrants, escaping conflict and poverty, want to go to Europe. It’s considered the closest safe region. But that’s gradually changing because of new restrictions on nongovernmental search-and-rescue missions off the coast of Libya, new money from the European Union to help Libya, Sudan and other African countries stop migration, and new EU training for the Libyan Coast Guard, which is cracking down on Mediterranean boat traffic.

All this makes the trip to Europe more costly and difficult. But it has not stopped would-be migrants in Sudan – especially the young – from plotting journeys to what they expect will be better lives.

The Lonely Fight in Sudan: One Official Works To Stem Migrant Smuggling – Without A Car, A Photocopier Or Any Staff

Ismail Omer Teirab has worked as deputy chairman of Sudan’s National Committee to Combat Trafficking for the past two years. It’s a high-profile job, and he’s had to deal with a lot of the criticism associated with funding from the European Union for anti-smuggling initiatives.

Founded after the Human Trafficking Act of 2014, Teirab’s committee is mentioned again and again in discussions around the Khartoum Process, a dialogue between countries along the migration trails from North Africa to Europe. Under this initiative, the EU has given more than 200 million Euros to Sudan to stop the flow of migrants… (read more)

The Smugglers’ Economy

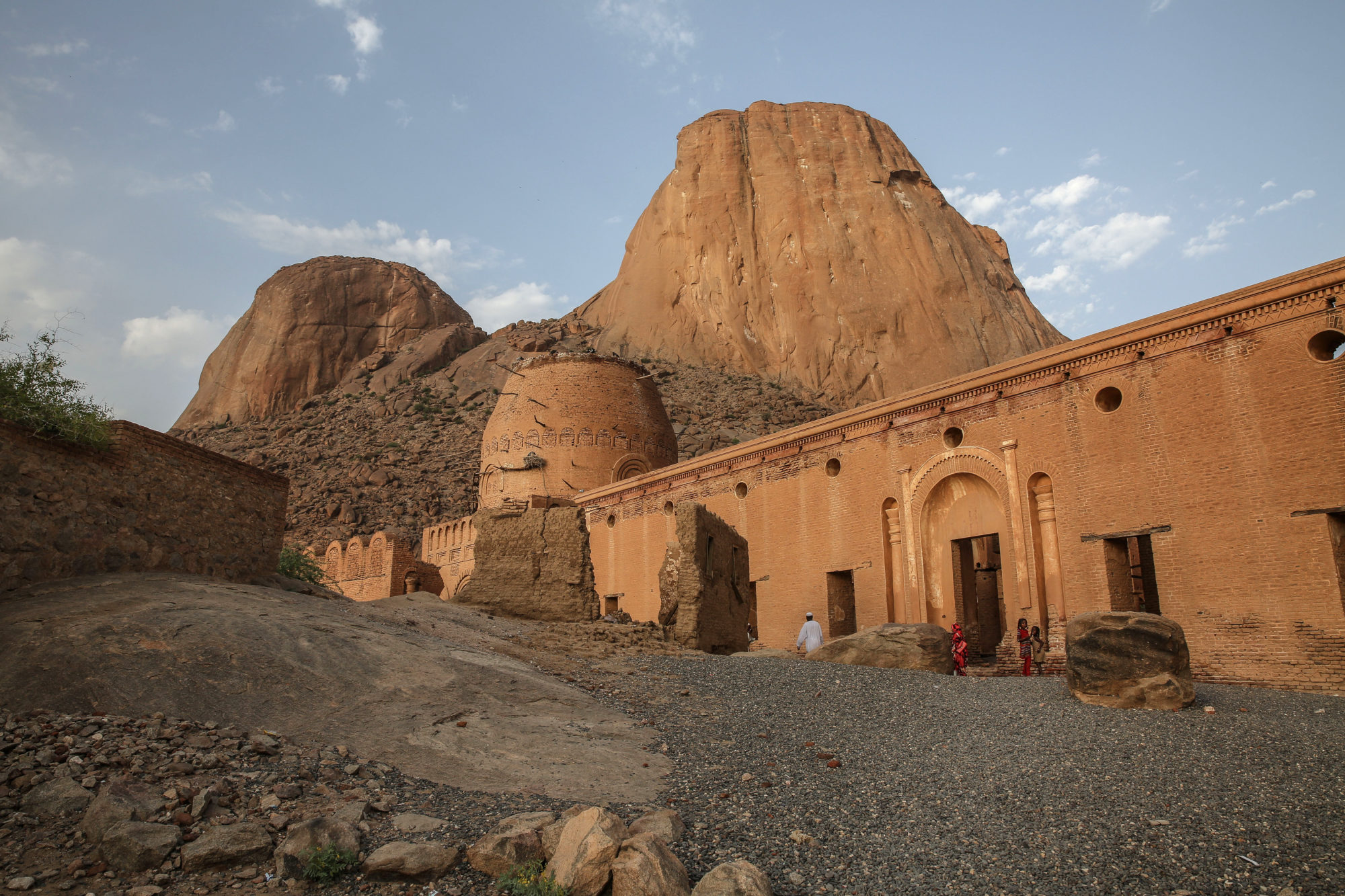

In Kassala, on Sudan’s eastern border, and in Sudan’s capital, Khartoum, smugglers are easy to find. In Khartoum, they’re often Eritreans who’ve made enough money to buy cars. Connections to smugglers are made through neighborhood recommendations; a meet-up is likely after asking a few key people.

“Smugglers are very organized, it’s organized crime,” said Ismail Omer Teirab, deputy chairman of the National Committee to Combat Human Trafficking (NCCT). He believes what makes them difficult to root out is that gangs often work with the nation’s security forces. “First they bribe policemen. Otherwise they couldn’t go through the checkpoints.”

For people like Nurah, who fled Eritrea because of forced unending military service and severe economic and social oppression, the journey from Kassala to Khartoum costs from $300 to $450 for boys and men, and $750 for women. Why the difference? Families have been willing to pay more to ensure the safety of women.

For those wanting to go farther, passage to Libya costs another $1,600 and $1,800; going all the way to Europe from Khartoum – in a smuggler’s run – costs as much as $5,000 — a fortune even for working refugees who earn as little as $50 a month as laborers.

When a ransom is added, the price skyrockets. And, If it goes wrong, some pay with their lives.

The one certainty is falling into steep debt to the money managers who facilitate the journeys. Migrants who brave the voyage often fall into the hands of militias operating a vicious slave trade inside Libya, where multiple governments and many tribes are locked in a struggle for supremacy.

Refugees and migrants who unsuccessfully attempted the journey to Libya said smugglers will often sell them to other gangs once they draw near the Libyan border. Pretty soon, they no longer know who’s in charge, and the terms of their “contracts” can change without notice or negotiation. Some migrants are held in detention, suffering malnutrition and physical or sexual abuse. Others are forced to work until smugglers decide the debt is paid.

“Traffickers don’t keep their agreements. They’ll increase or double it and sell them to other traffickers,” said one 27-year-old Eritrean, whose friends recently set out on the journey and an unknown fate.

Europe “is only a hope, a wish,” he said.

On The Rough Road in Sudan

It took two months for Helen to fully regain her memory after her first attempt to get into Libya.

The clarity of hindsight returned, and, in a cramped, unlit room in the Sudanese capital Khartoum, she sat slumped, her delicate features crumpling as she recounted a harrowing odyssey from her home country to the desert in the north. The 22-year-old Eritrean had set off in a group of 87 migrants, all eager to move on from the discrimination and exploitation they had experienced in Sudan. But now almost a third of them were dead or missing. “All of us lost our minds,” she said. “We couldn’t remember where we had been…” (read more)

Go Now, Pay Later

The Central Mediterranean Sea is currently the deadliest route to Europe. Some 600,000 people have crossed since 2014, while around 12,000 are feared to have died at sea. More than 2,800 are believed to have died so far in 2017.

Migrants and refugees in Sudan often originate in Eritrea. In Sudan, their movements are limited. They claim they face harassment by the police, who regularly round them up, threatening deportation unless they pay bribes.

“The police every day arrest Eritreans and Ethiopians here. They ask for your ID card, make you pay $50. If you have an ID card they might take it and cut it (in half), then charge you anyway,” said one Eritrean father.

“Some of the police live off refugees,” a Khartoum resident, who asked to remain anonymous, agreed. “They really get the brunt of it.”

Those who manage to get permission to work are often paid very little, and much less than a local would get.

The road to Europe is so difficult, however, that many who today are trying to get across the Mediterranean are the second generation, sons and daughters of refugees who came to Sudan years ago. They see their parents being paid low wages, and suffering discrimination, police brutality and corruption, and decide they don’t want the same life.

Meanwhile, smugglers search out young people and convince them to make the journey without telling their parents. ‘Go now, ask for money later,’ they tell them. ‘That way no one can stop you.’

“I hid it from my family. I won’t tell my parents until I get to Libya,” explained a 24-year-old woman with delicate features in Khartoum. She said her parents had properties in Eritrea they could sell, a sacrifice that would leave them with nothing but if she is caught, she knows they will have to pay. “I will be exposed to slavery and sexual violence if they don’t pay.”

Another 24-year-old, a nurse from Eritrea who wants to be a doctor, said she was aware of the dangers but “I know but there is no more miserable life than this that I am now living. I want a chance… a better life.”

Two weeks ago her 18-year-old sister tried to follow her to Khartoum, but was kidnapped on the Eritrean border. They have been told the ransom is $5,000, an impossible amount for her family. But she worries that if the ransom is not paid, the girl may be moved up to the Sinai desert in Egypt. Among Eritreans, there are rumors that there is a trade in organ harvesting in that area, although the UN Special Rapporteur for Eritrea said there is no evidence that proves those claims.

“There are many who tried to go to Libya and they are dead,” said Azgiamin Tesialassi, a tired-looking Eritrean woman with braided hair, speaking in a dark, stone house in a low-income neighborhood popular with refugees. “Some are lost in the desert and some at sea. For those who are dead no one can help.”

As she speaks, she repeats the words “delalti haisebat” – which means human smugglers in her language, Tigrinya. “Our children are being kidnapped by smugglers here.“

An Eritrean teenager sits on his bed in the unaccompanied minors section of Shagarab refugee camp, eastern Sudan, on July 20, 2017. (Photo by Sally Hayden)

Boys sit in their dormitory in the unaccompanied minors section of Shagarab refugee camp in eastern Sudan, on July 20, 2017. (Photo by Sally Hayden)

A young girl stands in a dormitory in the unaccompanied minors section of Shagarab refugee camp, eastern Sudan, on July 20, 2017. (Photo by Sally Hayden)

Eritreans play pool in one of the makeshift pool halls in Shagarab camp in eastern Sudan, on July 20, 2017. (Photo by Sally Hayden)

Children walk to school in Shagarab camp in eastern Sudan, on July 20, 2017. (Photo by Sally Hayden)

Stopping the flow?

“If trafficking is business now how can we make it non-profitable? I haven’t an answer,” the NCCT’s Ismail Omer Teirab said in an interview in Khartoum’s oldest hotel, the Acropole.

At least 100 people each month make it into Libya, Teirab estimates, though exact statistics are impossible to collect in a vast area with little technology and record keeping.

The NCCT was formed after Sudan voted in the much-lauded 2014 Human Trafficking Act. Teirab, a former teacher from Darfur, said he wants to run campaigns to educate refugees and Sudanese youth about the danger in courting smugglers. He has received minimal funding – not enough for an office, other staff members, or even a photocopier.

“Every day young people see videos of Europe on their phones now, how can we combat that?” he asks.

Jeff Crisp, a research fellow at the public affairs think tank Chatham House and the former Head of Policy at UNHCR, said it’s not impossible that if the Mediterranean becomes an impassable barrier, smugglers will begin sending people on new routes.

“It’s something a lot of people say: if one route closes it diverts into another,” Crisp said. “[But] it takes a while between one route closing off and then people taking up a different route.”

Among refugees in Sudan, there is little knowledge of the world outside the destinations already travelled to by their family or acquaintances from home. Most simply expressed the desire to keep moving until they found a safe space with opportunity. “I don’t know where would be good but I know I can’t stay here,” one refugee said.

There is evidence that more migrants from northern and east Africa are even finding their way to South America, by routes much more arduous than might be expected. In one neighborhood, families told of one Somali who ended up in Mexico, after he flew from Zambia to Brazil with a work visa. Another Somali travelled to Brazil from South Africa.

Another factor pushing migrants elsewhere is a growing recognition of the backlash against new settlers in Europe, and the magnitude of the Mediterranean crossing.

“Panic is the word I would use for the EU response to the whole refugee and migration issue over the last three years, it’s really not got its act together and it’s lurched from one thing to another,” Crisp said. “I think everyone thinks that there’s an importance in appearing and talking tough.”

Crisp added while it was obvious the EU was hoping people would no longer go on boats if rescues off the coast stop, “that really depends on how much information they have and what the smugglers and traffickers tell them.”

Tekulu, an Eritrean 24-year-old in Khartoum, is due to make the journey north soon. He said smugglers don’t tell refugees the truth about the risks involved with these journeys, or give them adequate information about what the situation on the other side might be. “With the traffickers – no one tells you exactly how people live as refugees and how they arrive. They just tell you things are good.”

He was waiting, camped out in a sparse compound that has been used by countless Eritreans on their way through Sudan. The four other young men staying there had been in Khartoum less than a month.

On Tekulu’s skinny bicep was a tattoo from the early days of his forced military training, the imprint carried out with a pen heated over a burning tire. “It was not more painful than what was happening” around us, he said bravely.

Given what he’s been through, Tekulu isn’t willing to shatter illusions for those who’ll no doubt follow him. “Even if I tell them not to come how can they stay here? It is good for me to keep quiet.”